When Homo Promos went to Edinburgh in 1988, the summer after the Section 28 campaign, we took up residence in the wonderful ‘Blue Moon’ café in Broughton Street, now long since closed.

The café, brainchild of the Scottish Minorities Group and the late Ian Dunn, combined meeting place, vegetarian café and campaign centre. I think the Edinburgh Switchboard was also based there.

It was crammed with frenetic activity, and we elbowed ourselves the space to do three shows for three weeks, with all the arrogance of self-centred thespians.

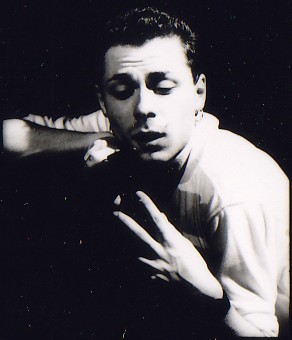

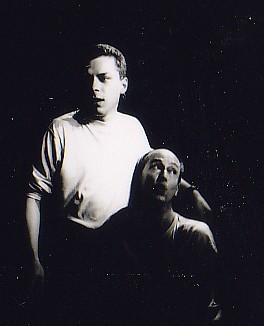

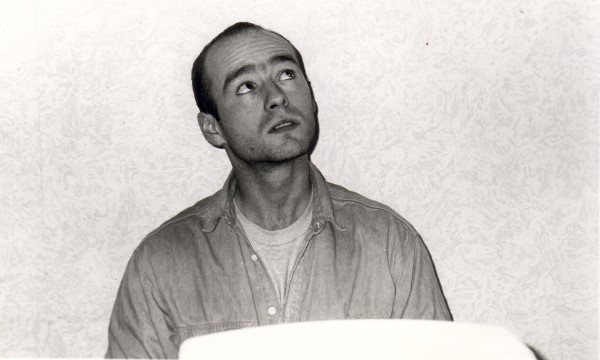

Lerv was written especially for the café space, and especially for Simon Kennett and me. Simon was in his early 20s, I was on the verge of 40, and the age difference played into this ‘vaudeville’ – one of my favourite words – of unrequited love, set to the soundtrack of Shirley Bassey’s greatest hits.

It was written very quickly in Edinburgh in the three days before we opened, and because of the pace demanded a certain amount of plagiarism from other shows I’d been in down the years – not necessarily my own.

I like writing site-specific shows and going into places which were not conventional theatres – indeed, where you might be surprised to find a show. We played on the fact that we were in a café by casting the two characters of Mutt and Jeff 1 as waiters.

The idea was that the audience shouldn’t know when the show started, and it would sort of creep up on them. Simon and I would be going round the tables, taking orders and bringing food, until at a secret signal was given and I would launch into the Bassey hit ‘Love… look at the two of us.’

The vaudeville would then play around, over, and occasionally under, the dining tables, tripping over, getting food all over our uniforms and appealing to diners for support or sympathy.

Over the three-week run, more and more improvisation crept in and Lerv ended up about 50% longer than it was when we started.

We didn’t care. We were happy. We were young and in Lerv.

This script, however, is the point of departure.

View the YouTube recording of Lerv.

Peter Scott-Presland (January 2021)

1. Mutt and Jeff were two American comic characters who went on to star in cartoons of the 1930s and 40s. I knew of them because my Uncle Bill only had two hairs on his chest, which he would proudly show off: they were called Mutt and Jeff.

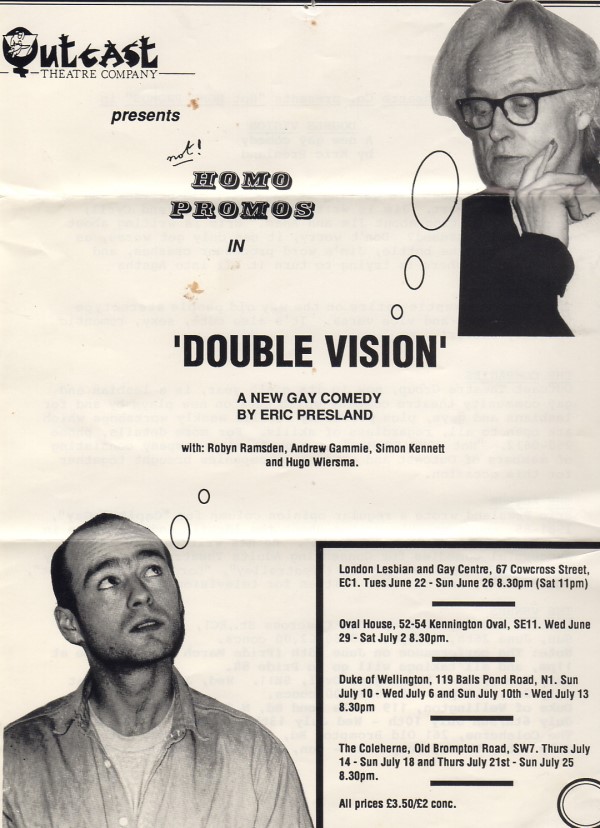

LLGC, Oval House, Duke of Wellington, The Coleherne 22 June to 25 July 1988

Double Vision is a one-act comedy on the theme of ageism, and the way that older gays look on younger gays, and vice versa.

Its basic structure was taken from a short sketch by American playwright Robert Patrick from the trilogy, ‘Lights, Camera, Action’, but expanded into an extended riff.

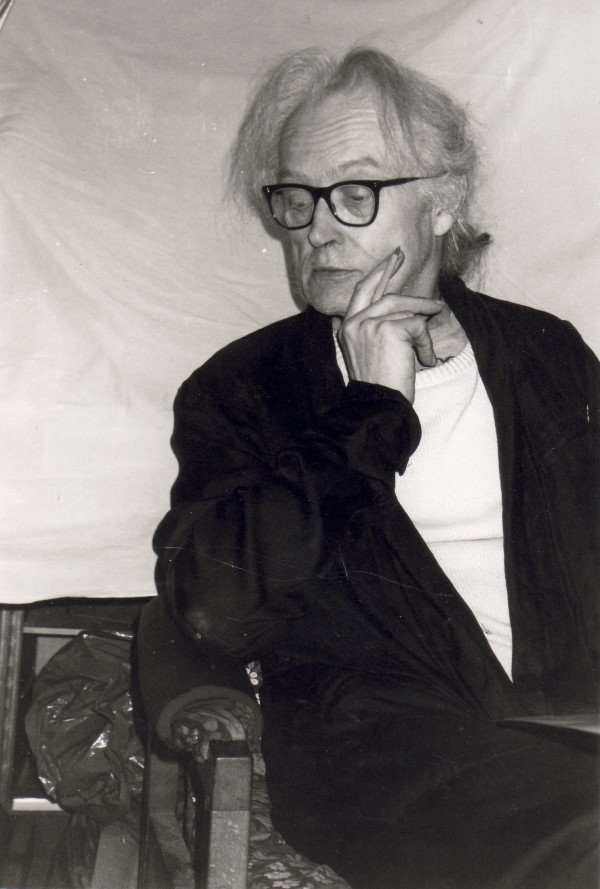

Robert Patrick is now virtually forgotten, but he was the powerhouse of both New York Fringe Theatre and Gay Theatre at the Café Chino from the early 1960s to the 1980s. Scores of plays poured from his pen.

Every Fringe company and every gay company owes him a huge debt for opening up the range of possibilities for both style and substance in telling LGBT stories. His Cheap Theatricks remains the one book of plays I reread for pleasure.

So, back to Double Vision. When you are a new company with its first play, you have few resources in terms of money, space or time. To describe it as mounted on a shoestring is an extravagance. We couldn’t afford shoestrings.

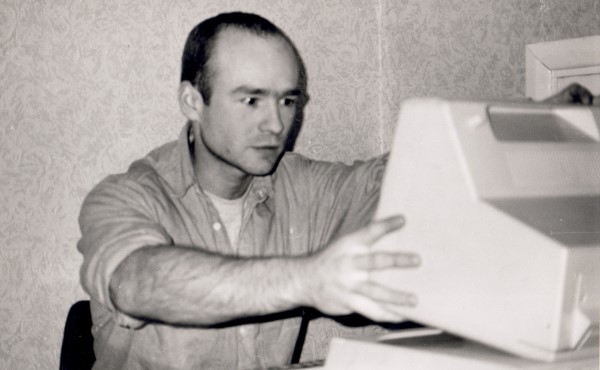

One of the reasons I wrote it the way I did was that all it needed was an armchair, a chair and table, a standard lamp and one of those new-fangled word processors. We used mine, which meant I couldn’t do any other work while the show was on. or had to go to the theatre early to do it.

Young Jim and Adam are getting it together; Gervase and Cyril are falling apart. Jim is writing about Gervase and Cyril; Gervase is writing about Jim and Adam. Eric is writing about everyone.

But who is writing about Eric? Confused? Don’t worry, things can only get more complicated, as Gervase hits the bottle, Jim’s computer crashes, and someone, somewhere is trying to turn it all into Agatha Christie. The play is cute, sexy, romantic, and very clever.

This was the first production which Homo Promos mounted. It was somewhat fraught, in that Robyn Ramsden, who was playing Gervase, found it impossible to learn the lines..

He was a lovely old hippy; whenever anyone asked him how he was, he always replied in a feeble voice, "A little better".

However, his brain was addled by too many years of heavy-duty dope smoking. So, the author had to step in at the last minute, between the dress rehearsal and the first night, and take over the part.

The Oval House, which was funded by Lambeth Council, was scared of falling foul of Section 28, and insisted that we had to change the name of the company. We could hardly complain because that was the very reason why we chose the name; to sail into the eye of any storm created by Section 28, and to highlight its absurdity.

So, for the purposes of this show at The Oval, with the aid of a felt-tip marker, we called ourselves 'not Homo Promos’ (see poster).

Peter Scott-Presland (January 2021)

The script is available for performance by other companies. Contact Us for more information. Running time: 55 minutes.

Written and directed by Eric Presland

Gervase - Robyn Ramsden/Eric Presland

Cyril - Hugo Wiersma

Jim - Andrew Gammie

Adam Simon Kennett

Lights and Sound - Eric Presland/Philip King

‘Lerv’ and ‘Grand Passion’ are both written by Eric Presland and performed in a café while people are being served food and drink. In ‘Lerv’ one of the actors is busy wiping tables and clearing away plates within the context of the play. This works well and breaks down the usual barriers which exist between performers and audience.

The company are [sic] a gay theatre group but their subject matter has a wider appeal. However, the specific reason for their creation, to fight against Section 28, infects their scripts and the protest element feeds in subtly.

‘Grand Passion’ is the more serious of the two. The subject matter is jealousy. In passing, the theme of AIDS is touched, but in a natural and understated way. My main criticism was the weakness of the acting. It was a little under-rehearsed and Eric Presland lacked the charisma to pull of [sic] his script with the conviction it deserved.

Worth catching over a lunch or a dinner at the Blue Moon (café).

BS, Edinburgh Festival Times, 30 August 1989

* * * * *

Eric Presland’s monologue ‘Grand Passion’ is a moving, gusty soliloquy on jealousy, heartache, suspicion, envy and all those other little gremlins lurking beneath any relationship, in this case a homosexual one.

Behind the comedy simmers the message that without honesty, or at least real communication, a modern relationship is doomed.

This is a powerful play, often threatening, sometimes funny – and theatrically a winner.

John Hyde, The Scotsman, 28 August 1989

* * * * *

From one-man cabaret to one-man plays, another oversubscribed field. Everybody seems to have a play inside them; or alternatively, it’s just cheaper if you’ve only got one actor to pay.

The best of these that I saw was ‘Grand Passion’, a short monologue by and starring the ubiquitous Eric Presland, who in an intimate, intense and personal forty-five minutes, laid bare his jealousy as his lover is fucked by another in the room next door.

This was staged in a dingy committee room beneath the otherwise smart and wonderful Blue Moon Café at Edinburgh’s Gay Centre; the condition may have been raw, but the results were uncompromising.

Presland’s wonderfully titled Homo Promos company also staged two other shows there, and I wish I’d seen them.Mark Shenton, Pink Paper, September 1989

* * * * *

Vaudeville may not be an art form often associated with the Fringe, but it seems to serve this production well. Boy meets boy as an older guy – ‘I’m a mature student’/’Senile more like’ – quips the younger object of his affections, boom-boom – declares his love.

There are lots of funny lines based on the gay sub-culture as Jeff tries to interest Mutt by inviting him to see Torch Song Trilogy, an Orton play, the Mapplethorpe exhibition, the Berlin Philharmonic.

Being gay vaudeville, there are some simulated sex scenes which seemed overly school-boyish and passé. Though some of the jokes fell flat, most of the quick retorts were very funny.

An extended satire on Mutt’s unrequited attraction to furniture is very clever, as is actors Eric Presland and Simon Kennett’s use of the Café’s space.

John Hyde, The Scotsman, 24 August 1989

A tale of two writers: Jim, a handsome Isle of Dogs queen tapping out his first novel on a WP, and Gervase, a wasted old cynic scribbling his last with a biro. Gervase is heavy on the Scotch, and thinks he is losing his long-term lover; Jim is heavy on the post-structuralism and thinks he is gaining the love or at least the admiration of last night’s boy from The Bell.

The twist is that each is a character in the other’s novel. Their attempts to rewrite each other’s lives allow Eric Presland to play telling games with his favourite theme: that we gay men should escape from the prescriptive fictions of stereotyping (especially stereotyping to do with age and attractiveness) and explore our capacity for odd couplings, independent loves and general amused respect for each other.

The show is simply played, in a now recognisable style of unapologetic gay amateur dramatics, which is either infuriating or endearing according to taste. When the comedy is as clever and pertinent as this, I think you’ll be endeared.

Neil Bartlett, Time Out, 5 July 1988

* * * * *

Leave the leather crowd cruising downstairs at the Coleherne. Go upstairs and catch Eric Presland’s gem, before its run ends on Sunday. Its satire of the stereotyped assumptions old and young gays have about each other is clever, witty and uncomfortably astute.

Personable Jim, creation of hack novelist Gervase, is completing his first novel. Enter toy-boy Adam. The two melt into each other’s arms with all the clichés Gervase can muster. Adam moves to Jim’s word-processor, savouring every word keyed in by his idol.

Jim’s novel tells of two jaded lovers coming to the end of the road; one is taken-for-granted Cyril, the other Gervase, a writer living only to pour cynicism into his fictional lovers Jim and Adam.

If this is confusing, it gets worse. Fiction and reality co-exist in the lives of these characters, but never for a moment does Presland lose his audience.

The acting space is divided. In one half, Gervase sits morose and writes. In the other, Jim and Adam enact incidents created by their author that lead to their separation. And vice versa. Gervase and Cyril work through the breakdown of their relationship according to Jim.

A superb double act between Jim (Andrew Gammie) and Gervase (Eric Presland) is the play’s high point. The audience finds itself drawn into a confrontation in which the characters struggle to compromise with their self-opinionated selves and face a few home truths before being able to write the happy endings for each other that will bring their lovers back.

What the production lacks in gloss it certainly makes up in spirit, sensitivity, timing and humour. Simon Kennett as Adam scores wonderfully with laughs. His naïve deadpan delivery of lines such as: ‘I love history. It’s so – old’ does full justice to Presland’s parody.

The play’s a winner. Don’t miss it.

David Terry, Capital Gay, 22 July, 1988

* * * * *

The cost of one costume at the Palladium could keep Eric Presland’s four-hander “Double Vision” running for three months or more. Only the short-sighted could prefer the costume; Mr Presland’s play concerns the fearful egocentricity of writers – in this case one of them young and one of them middle-aged.

The particular vanities and empathies of the characters are well explored – but what was most interesting about this work was in the changing swings from high comedy to tragic consequence that the audience was subjected to.

This was a thought-provoking piece that was funny, didactic and oddly moving. And here again, we saw a cast that was at one with its subject matter – which often challenged the audience’s intelligence without ever patronising it.

My advice is to forget the dinosaurs of the West End and look for the rainbows on the fringe. Look after your own. Support Osmond, Presland or Lorca. They are cheaper on the pocket, good for the heart and don’t bludgeon the brain.

Tom Wakefield, Gay Times, Sept 1988

* * * * *

Life as fiction; fiction as life. Art before life? Or life before art? Whose life is it anyway, when characters are at the beck and call of their creator i.e. the author. With a nod here (well, maybe a sidelong glance) at Pirandello and ‘inspired’ (if that’s the word) by Gore Vidal’s meditations on post-post-structuralism.

Eric Presland’s spoof on the game we play chatters along amiably for an hour or so, as four gay characters – two authors, themselves the creation of each other, and their two lovers – play out contrasting lives and loves, dropping into one another’s stories, dropping out, and wondering who’s actually pulling the strings.

It’s ingenious enough, clearly produced on less than a shoestring, and offers a mild tongue-in-cheek reflection on some familiar themes about positive images, gay romance, fantasy and the relationship of life to art.

Just about enough to stimulate the brain cells before Wimbledon Match of the Day.

Carole Woddis, City Limits, 5 July 1988