I came to London in 1979. I say ‘came’, but I had been born and brought up in the suburbs, in East and North Finchley. Yet when I returned as a card-carrying faggot, I came back to Inner London (Hackney, Islington, Lambeth, Lewisham) which was in essence a completely different city. Social, not isolated in families, and with an altogether more flexible set of morals.

I arrived in a threesome with Anna and Steve in June 1979. It was not stable, because I at least lacked the social and emotional skills to keep that going for any length of time. Too much ego.

And one impetus to the crack-up came from Steve, who one night met someone at a pub and brought him back for the night.

Although I was thirty, I behaved like someone half that age. I was so used to being the King Rat, so blithely accepting of my right to get exactly what I wanted, that this left me reeling with sexual insecurity. I had known jealousy before, but never of this visceral kind.

So, I started writing that very night with the bed springs creaking next door. Never was play more autobiographical. I’d done about four pages by the time I collapsed exhausted on my own, empty, bed.

By the time I returned to the play three weeks later, Steve had moved out. The one-night stand had developed into something else, and indeed lasted for years. My worst fears of that night were realised.

But in the meantime, I’d had the chance to see it in some sort of perspective and appreciate what I had on my hands.

It was, I realised, a riposte to a play by Robert Patrick called One Person.

That was a monologue which was very popular in the 70s. Gay Sweatshop had done it at the Almost Free in 1975 and wherever there was an actor without a company who needed a virtuoso piece which required no set or costumes, but just a space, this was a first port of call.

Patrick after all wrote for the tiny Café Cino in New York, and pretty much invented gay theatre on the Fringe. I had performed One Person in Birmingham, and it was popular.

I came to dislike the piece because the more I thought about it, the more self-indulgent it seemed. The Author, the solo character, dissects what went wrong with the love of his life, for the benefit of the lover who is sitting in the audience expecting a different play.

What a shitty thing to do! To create cringe-making embarrassment for someone who is powerless to answer back. Of course, they could get up and walk out. I would, but then there would be no play. At the end (spoiler alert) the Lover goes off with someone else, leaving the Author putting a brave face on it à la Bette Davis.

Patrick, the Author seems completely unaware of how self-centred he is. The title of the play refers to a line:

“I was one person, and you were one person, and then we - we were one person and then - then what? What happened? We were one person - and that person - I suppose - became lonely.”

The problem is that the one person who was ‘we’ was the overbearing Author. There was no space for the ‘you’ in the ‘we’. More than that, it seems clear to me that the one who became lonely was the lover, not the gregarious author.

I wrote a long letter, probably arrogant, to Robert Patrick telling him exactly what I thought of the play. After that, he referred to me as ‘the boy who doesn’t believe in love’. An audience, seduced into an easy pity, identified with the Author. His rejection chimed with their various rejections. I was on the side of the Lover.

So Grand Passion became the same story, focussed on the moment of rejection, and stripping away the soft focus from the sexual element.

I never believed in the sweet wistful resignation of Patrick’s Author. Unless you see the whole context of his play as a particularly sadistic mind-game of revenge.

I wanted to re-establish the rawness of the feeling of jealousy, the way your nerve-ends scream, the way the brain seems flayed.

And at the same time, locate that in a character with pretensions to being ‘civilised’ and ‘liberated’, who pays at least lip-service to all the tenets of the Gay Liberation Front about abolition of monogamy and the family unit and patriarchy.

That to me was the interesting tension, and what gave the play its dialectic. That is why it is sub-titled ‘An Argument for One Character’.

I wrote the first version in 1979. By 1989, when I rewrote it for performance in Edinburgh at the Blue Moon Café, the AIDS epidemic had intervened. This lent an urgency, a particular locus, to the anxieties about ‘infidelity’. It smeared a ‘rational’ veneer about infection over what was an essentially atavistic insecurity.

In the use of condoms, it also provided a focal point for a climax which was shocking to its original audience, and I hope remains so.

Looking at the play from a distance of thirty years, it seems to give away more about me than I realised at the time or feel comfortable with now. There is a strange mismatch between the physical age of the character and his psychology, which seems in its concerns with being ‘unattractive’ to belong to a much older man.

Or maybe that was simply a result of two versions written ten years apart and failing to integrate the two. Maybe a second revision is in order.

In our less rigid world, where there are forty different words to describe gender identity, perhaps the concerns of the play appear dated.

Maybe younger people will have no idea what I’m going on about.

I suspect that however you define your relationship, for many people the desire to share with one person, and the fear of losing that person, still weigh heavily.

I hope so. Anything else is insufferable arrogance.

Peter Scott-Presland (April 2021)

All work is copyright of Peter Scott‐Presland. Anyone interested in performing all or part of it should Contact Us

Read the Script

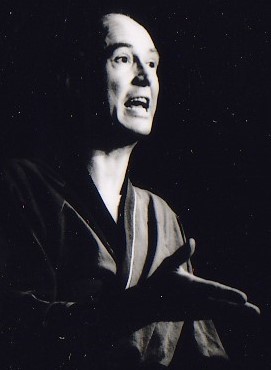

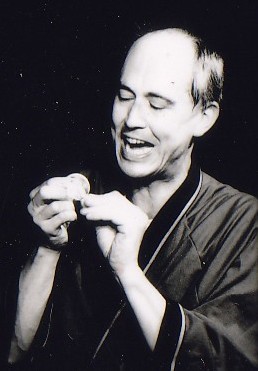

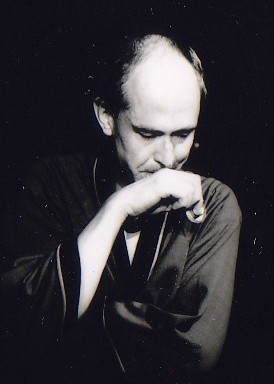

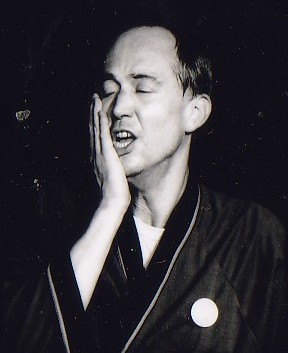

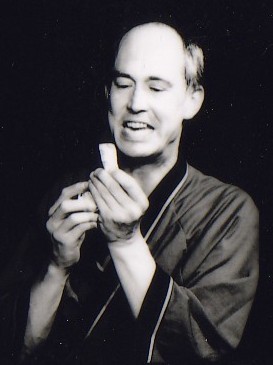

All images are of Eric Presland in Grand Passion