Nearly forty years ago, I was afraid most of my friends were going to die. There was an entire floor at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital just for people with AIDS. And the surge of funerals had begun.

So, I sat down in a grotty hotel outside of Windsor and began writing a play about a Gay man who was dying of AIDS.

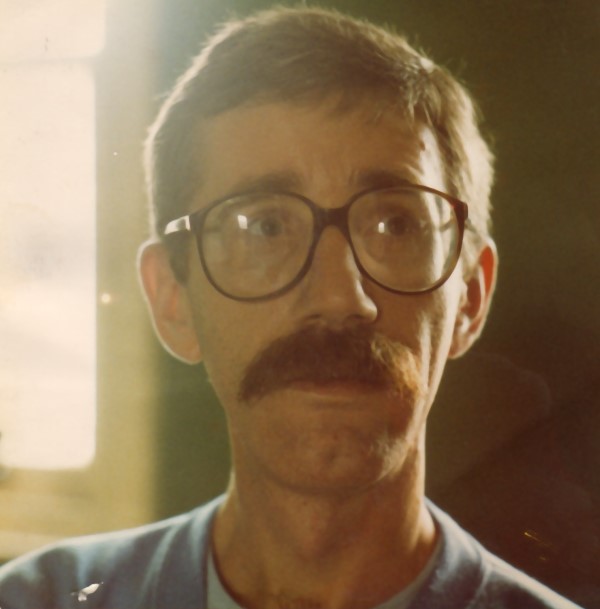

I was inspired by my friend Arthur Stutsman, who had just been diagnosed with it when I left Baltimore to move to England with my lover.

I was devastated. I was frightened, furious and I had to do something. I wrote Anti Body in about three weeks. Then I sent it to a London theatre company called Consenting Adults in Public.

What I had to do was narrow the scale down, write the story of one man, William Davis, and what happens to him. The protagonist was based partly on Arthur, and also on my father, who died of lung cancer in 1976. And the other characters were mostly activists, his friends that were his family, his mother and brother, and Gay doctor. That was Anti Body.

Eric Presland (now Peter Scott-Presland) read it when I sent to Consenting Adults in Public, and he wrote me a letter I still treasure. He wanted to get the play done, and he helped to re-write to set it in England. He also took on directing it, and the group managed to get Greater London Council funding for it as well.

Anti Body was a way to sound the alarm as well, to shout the message that sex with someone with the virus could kill you. That was not a popular declaration in 1983.

I did update the show, and so did Peter, as best we could, but safer sex wasn’t even a thing in the spring of 1983 and barely known in the fall of 1983, when Anti Body was produced at the Cockpit Theatre, off the Edgware Road, London, in October.

Back in 1982 there were no effective treatments, no support outside of the Gay and Lesbian community and some plain terror abounding for those that had some idea how HIV was transmitted. If you got it, your immune system collapsed, sometimes suddenly, sometimes more slowly, and rare diseases could flourish.

By January 1983, when I wrote the play, there were 1,000 cases in the USA and 60% of those people were dead. The virus was busy rocketing around the world. The villainous Reagan Administration was ignoring it, while my buddies died. It was going to be up to us to take care of each other as downplaying the crisis got worse.

Meanwhile, I became an AIDS educator, teaching folks that I thought sex was grand but there needed to be a change in how we played with each other. LGBT, heterosexuals, everyone.

I choose to believe that William’s curtain speech did have an impact, that along with other warnings and information, reduced the death rate in London.

The cases in London didn’t increase at the same rate as in the US, and I know that there were people who told me that they began using protection after 1983.

My play was the first of the myriad ways in which the British helped slow down the virus. Later, Larry Kramer’s Normal Heart did an outstanding job sounding the alarm bell in 1985, and it remains my favourite play about AIDS, with Tony Kushner’s Angels in America very close. The best book is Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On.

The radio version of Anti Body, re-written extensively by Peter and submitted but never performed on the BBC, is my absolute favourite. The tragedy remains, but the characters are more three dimensional and the humour is at once more pointed and poignant. Since this version includes some of that script, I have no doubt it shall be the best of all.

Mortality rates have dropped, but the death toll now stands at 33 million. Most of those who die don’t have access to testing and treatment. We still need to talk about AIDS even as we deal with the Coronavirus pandemic. To this day I still wish that I’d never needed to write it.

But I’m extremely glad that it’s being done once again in the country where I first wrote it. Forgive its flaws, but unlike Puck I dare not reassure you that it was a dream. Do not slumber, wake up. And play safe. Please.

Your faithful and obedient servant

Louise Parker Kelley (February 2021)

In early 1983 we didn’t even know what to call it. The scientists were still arguing as the US, in the form of Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute in Frabce, squabbled over who discovered what. It was heavy. There were accusations of theft and lawsuits.

At stake was personal and national prestige, and funding. Patients seemed to be low on the priority list in this clash of egos. So, what the hell was it? HTLV3? GRID? LAV? HIV?

How can you fight something which doesn’t even have a name, let alone a cause? There were rumours that it spread in the air, you could catch it off lavatory seats, and sharing towels. It took a year to get to the point where it was generally agreed that body fluids had something to do with it. But what exactly did that mean? What was the transmission route?

The earliest preventive action advocated was simple: Give up sex. For a generation which had spent twenty years and more fighting for the right to have sex, this advice was a non-starter.

There was no reliable test for whatever it was. The best that could be offered was, get yourself checked out. Again, this fell on stony ground. What was the point of testing for an unnamed disease for which there was no treatment and no cure?

Despite this, and the complete absence of interest in the mainstream media, lesbians and gays started organising, tentatively at first but with increasing confidence. The Terrence Higgins Trust started as a small group of Terry’s friends in August 1983, a year after he died.

Capital Gay started carrying stories, and later a regular weekly column by Tony Whitehead. It was quite clear that in a friendless world we were going to have to fend for ourselves.

The first stories about the mystery disease were in a gay publication (New York Native, May 1981), and it should also be remembered that many if not all the doctors involved in treatment at St Mary’s Paddington and the Chelsea & Westminster Hospitals were gay. But we knew jack shit.

The script of Anti Body (or AntiBody – the spelling has varied down the years) that Louise Parker Kelley sent me in 1983 was angry, well-informed, opinionated and urgent. After all, she had lived in Baltimore, near John Hopkins, one of the pioneer research and treatment centres.

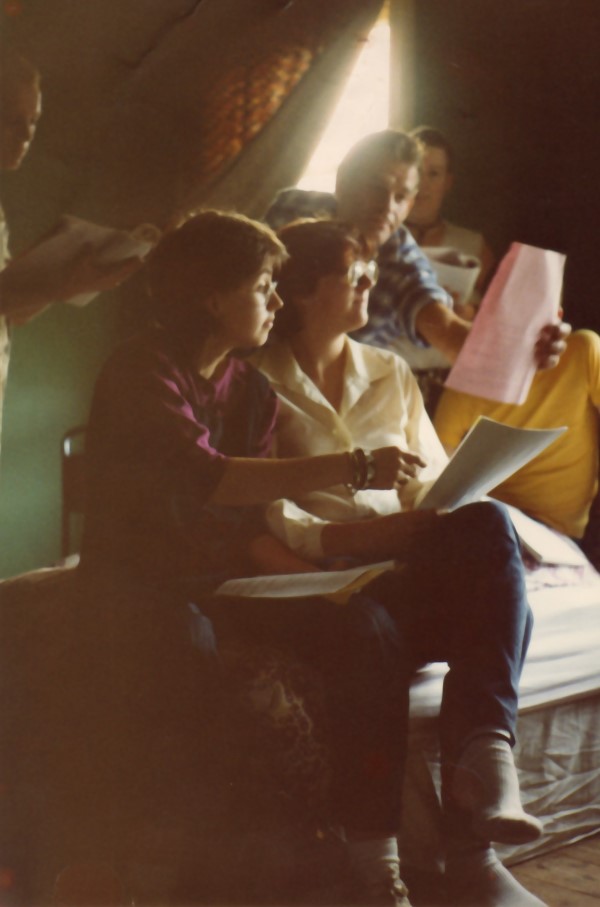

There was never any doubt that it had to be done, and immediately. This was a problem because the play needed production money and we’d always operated without it.

Thankfully, we had just acquired Neil Bartlett as a part-time support worker, and Neil had the experience and hutzpah to organise the grant application to Greater London Arts, and the subsequent theatre run and following tour. The money came through surprisingly quickly.

When I first read the play there were around fourteen diagnosed cases of HIV/AIDS in the UK. By the time we went into rehearsal there were twenty-nine. On the first night there were about forty. America’s cases were in five figures.

Michael Callan and Richard Berkowitz published How to Have Sex in an Epidemic in May that year, which was the first book to advocate safer sex. In the UK, the Gay Switchboard was advising callers to avoid having sex with Americans.

Looking at the script today, all this confusion and the speed with which events moved, stands out starkly. In addition to its merits as a play, it is an accurate representation of how it all felt at the time; particularly in the sense at the beginning of Act One that it is something to be laughed off, not that serious, followed by the chilling realisation through the play that 40% of those infected will die, and that William is one of the 40%.

The play also shows how bad we were (are?) at dealing with the prospect of death. This was particularly true of gay men; lesbians coped better, it seemed. I responded to many aspects of the play. I loved the fact that it was set in a real, politicised community.

These people had a community newspaper, organised Pride parades, joined organisations, and argued. Nor was it only about gay men; there were lesbians involved in this community, who shared the pain. There was a mother, and a brother; nobody was exempt.

Having a gay doctor as a character was pretty cool too. It faithfully reflects the passionate arguments about the issues of monogamy and promiscuity that arose, and of course it crams in a hell of a lot of information about a disease of which most people knew nothing.

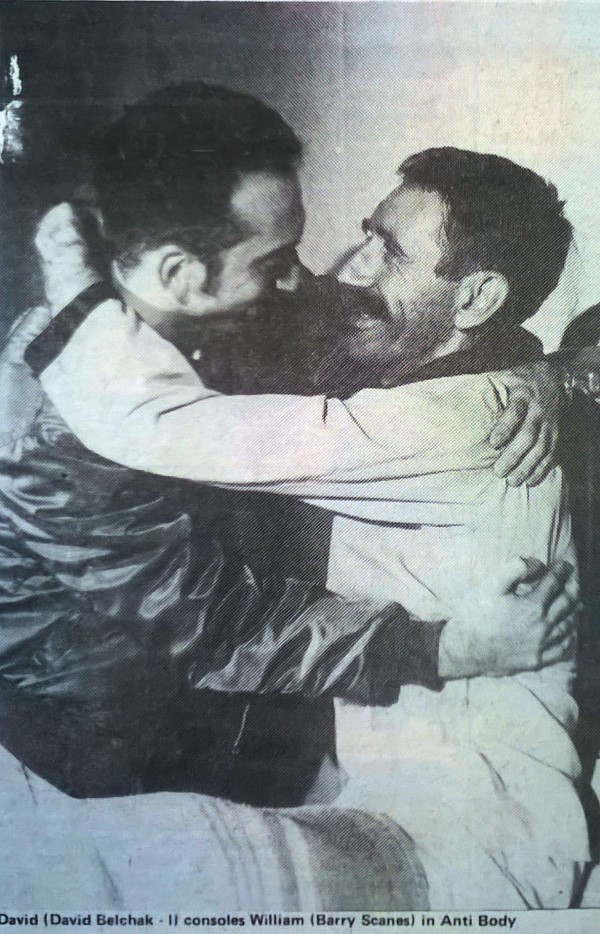

But the true triumph of the piece is to take an inexorable progress towards death, and to create an assertion of will in the face of that death. In spite of the odds, it is an affirmative play.

Make no mistake, this is a significant piece of our history. There is no doubt that this is the first play about HIV/AIDS to be produced in the world. And believe me, we’ve looked for predecessors.

If we’d known how important it was, we’d have kept better records. Louise, after much rooting around in Silver Springs, came up with her original script, minus twenty pages. Interestingly, there is no mention of safer sex in it.

I was very insistent that the play needed to be adapted for a British audience. If it were presented as written, it could be dismissed as something exotic, nothing to do with us Brits. I helped to write that adaptation, but no script of it survives as far as we know.

I do know that it had by this time acquired a powerful speech about safer sex, and that for some reason we made William’s ex-boyfriend Irish. This drew the wrath of several Irish activists down on us, accusing us of fake ‘Oirishry’. Not the accusation to throw at an author named Kelley.

In truth, seizing on this detail was displacement activity on the part of gay men uncomfortable with the notion that they might have to modify their behaviour.

After the production I wrote a 90-minute version for radio which was sent to the BBC in Spring 1984. After six months’ silence, I timidly wrote to them to enquire if there was any progress. They had lost it. It turned up two years’ later, returned with a note attached to say that it was out-of-date.

That radio version does survive, and I will post it on the website in the future for comparison. I have used some parts of that to paper over the gaps in the original. If this version we’re presenting for Zoom is a bit of a mongrel, it is still as faithful as we can make it to the 1983 UK production. And mongrels are lovely dogs.

There is one egregious error. In transferring the action from Baltimore to London, I did not take sufficient account of some of the differences in the social and political set-up. Louise castigated her local gay press for downplaying the

I should not have allowed this to stand, because London’s weekly freesheet Capital Gay was absolutely in the forefront of coverage of AIDS/HIV from 1983 onwards. I’m convinced that it saved lives, as well as supporting all the other organisations which sprang up.

It is true that other gay publications were not so quick or thorough on the uptake. Nor is it fair to blame the messenger if the message doesn’t sink in.

If I were to go for a definitive rewrite, I think I would set the play outside London, maybe Liverpool or Birmingham, to get a more accurate equivalent to ‘Bawmer’, as the locals pronounce it.

More mysteries. Where did that production visit? QX magazine mentioned in an article on Neil that he’d “led a national tour” of the play, but he doesn’t remember it. My mind’s a blank too. I remember going to Winter Pride, and to the London Monday Group at The Chepstow in Notting Hill.

Surviving members of the cast recall Brighton, Amsterdam (really?), and Liverpool. Anybody who can flesh out more details, please get in touch with us. As it stands, “national tour” seems a bit inflated.

As I write this, Russell T Davies’ series It’s a Sin, about the onset of AIDS/HIV in Manchester, is coming up to its last episode. It’s had almost universally good reviews, but I have held off watching it until after we’ve done our Zoom performance of Anti Body on 2 March 2021.

Davies is one of our finest screenwriters and just old enough at 57 to remember what the start of the epidemic was like, but I fear the process of going through the BBC production mill may have bowdlerised it. By contrast, Anti Body is the real thing.

Peter Scott-Presland (February 2021)

Read the Script

View the YouTube recording of Anti Body

Back to Top