It’s funny how you mishear things when you’re only half listening. Once I was wrestling with a newspaper column close to a deadline, with the radio playing in the background. I was startled to hear on the news that fighting had broken out in Debenham’s, and it wasn’t even the first day of the Sales. The newsreader had, of course, said ‘Lebanon’, in an item about Israel aggression against its Arab neighbours.

I was reminded of this when, half‐listening to Radio 3 while working on the libretto for Two Queens. I heard Matthew Sweet talking in a slot called Time Travellers, where some quirky little historical morsel with a musical connection is briefly aired by a guest.

He was telling the fascinating story of how Ivor Novello, golden boy of British musical theatre of 30s and 40s and the prettiest man in England, was sent to prison for fiddling his petrol coupons during World War II. It almost certainly cost him a knighthood.

At the time no‐one was allowed petrol unless they were doing work of national importance. Novello pleaded that he needed his personalised Rolls Royce because he was boosting morale, but to no avail.

Enter Grace Constable, a besotted fan, who overheard him at the stage door lamenting that he couldn’t motor down to his place in Maidenhead at the weekends ‐ he held regular orgies there. To ingratiate herself with him, Grace suggested that he should lend her firm the car, they would get petrol and use it in the week, and he could get off with it at the weekends.

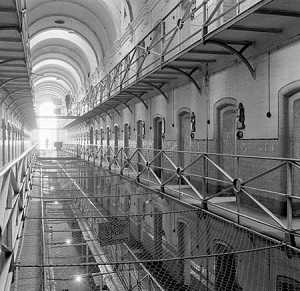

It was a cheeky suggestion from a typist under a false name pretending to be far more important in the company than she was. They knew nothing of it when the fraud was discovered, and Novello had the misfortune to come before a magistrate who hated musicals and homosexuals with an equal passion. As a result, he got twenty‐eight days in Wormwood Scrubs Prison.

Matthew Sweet said ‐ and I may have misheard this ‐ that he interviewed ‘Mad’ Frankie Fraser, psychopathic sidekick of the Richardson gang. Charlie and Eddie Richardson ran one of the most violent criminal set‐ups in London, second only to the Kray Twins. Pulling nails with pliers and cutting off toes with bolt cutters a speciality. Fraser claimed, according to Sweet, that he briefly shared a cell with Ivor Novello. I nearly fell out of my chair.

And it got better. Again, according to Fraser/Sweet, Novello was very distressed at being in prison, and nervous of meeting the other inmates, but as he was going down to lunch from his cell the first day, all the prisoners lined up and sang We’ll Gather Lilacs to welcome him.

That clinched it. In my mind I heard the humming chorus from Madame Butterfly. There had to be an opera in it.

That was the moment when the complete project of A Gay Century came swimming into focus. We had 1900, 1918 and 1936 ‐ and now here was 1944. Later I realised that this story couldn’t be entirely true, to say the least. Novello’s most popular song, from Perchance to Dream, didn’t see the light of day until 1945, a year after imprisonment, so there was no way that the cons could have known it. On the other hand, they would have known Keep the Home Fires Burning.

I read Fraser’s self‐serving memoirs; all three volumes of them. He claims acquaintance with Novello, but no more; he also denies knowing that he was gay, which from someone who spent nearly half his life in the nick, with all the goings‐on which that implies, is frankly incredible.

He seems the kind of ‘celebrity rough’ who would tell anyone in the media what they wanted to hear. But still, it was too good to let go. The problem was, what could connect the effete, dreamy theatre queen with the tough spiv with a penchant for inflicting pain?

I decided that the clue had to be in Fraser’s prospective hospital treatment. The authorities had decided he was so uncontrollable, so irredeemable, that he needed some form of shock treatment to subdue him. He was to be sent to Banstead Asylum for ECT.

For any gay man, aversion therapy of this kind would have been part of the terror with which they lived at the time; many who came up before the beak for importuning or gross indecency would agree to have ECT or drug therapy (‘chemical castration’) to avoid longer prison sentences. They knew not what they were letting themselves in for, but their stories of their torture after the event went the rounds of their friends.

It loomed enormous in the collective gay conscious. Ivor would have known people who had been on the receiving end, though his natural bent for escaping anything unpleasant would not have allowed him to dwell on the subject.

To this great encounter I added Ivor’s weird and wonderful mother, Clara, who died a year previously. I needed someone in whom he could confess.

She was a music teacher and voice coach, and ran a strange choir called the Welsh Grandmothers' Choir. She was convinced that these Welsh Grannies were destined for stardom and would bring World Peace.

Ivor spent much of his life bailing her out financially from these disastrous escapades.

This opera is the first in which Victoria does not appear either literally or figuratively; both Ivor and Frankie are implicitly opposed to Victorian values.

However, the connection to Wilde, through the prison itself, carries on the theme of the contiguous and collective gay experience throughout the century. And we are not finished with Wilde even yet.

Life in the 21st century is a far cry from the early 20th century. Everything is now ‘on tap’ and it is easy to forget that even the simple pleasures were not as simple as we now take for granted.

His first ‘hit’, written at outbreak of war in 1914 with Lena Guilbert Ford as his librettist, was Keep the Home Fires Burning (originally entitled Till the Boys Come Home). This, perhaps the most patriotic and enduring of songs, was just the beginning of a superb musical career with songs that still can tear at the heart strings even today, though his theatrical melodramas that featured them have somewhat faded in stature.

In Home Fires it would have been all too easy to steal from the maestro, but I have only dipped briefly into some of his enduring music, with the single exception of the prisoner’s chorus (Keep the Home Fires Burning).

I chose a harp as part of the instrumental ensemble to give a feel of Ivor’s Welsh background and the two saxophones to throw a nod to the era through which he lived (when instruments like the saxophone became quite popular in musical theatre and in live music), although he himself never used one in his orchestration.

I don’t consider myself a musicologist, (I leave that to others!) but for this work I have freely utilised two musical idioms: firstly, a ‘tritone’ (otherwise known as an augmented 4th or diminished 5th) which was originally banned in Renaissance church music as ‘diabolus in musica’ or ‘the devil in music’ and secondly, a ‘major/minor second’ (or diatonic tone/semitone) which I feel together give voice to the underlying unjustness of Ivor’s imprisonment in that unenlightened time.

Resources: Performers ‐ Soprano, Tenor, Baritone, Bass, Offstage prisoners’ chorus (pre‐recorded). Players ‐ harp, alto and tenor saxophone.

Sources:

Read the Script

This is a video of the Cockpit performance - September 2023

This is the Score:

Ivor Novello opera controversially scrapped by his former prison. Read the Classic FM article

All work is copyright of Peter Scott-Presland and Robert Ely.

Anyone interested in performing all or part of it should Contact Us